Suzannah Lipscomb looks beyond the stereotypes that surround our most infamous monarch to ask

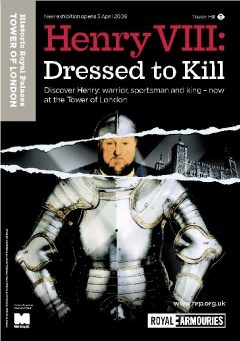

Who was Henry VIII and when did it all go wrong?Article reproduced from History Today, April 2009. When it comes to Henry VIII, we all think we know him and all there is to know about him. His much-reproduced full-length image, the profusion of TV shows and films depicting him, and the number of fictional and historical books set in his world make him ubiquitous and easily categorized. A whole set of clichés, truisms and fallacies accompany that famous silhouette. As a character, this infamous king both repulses and fascinates us. The ‘couldn’t-make-it-up’ quality of his personal life, his vast girth, larger than life persona, grandeur, pomp, arrogance and appetites make us strangely proud of this hyper-masculine, fabled monarch. And yet, much of what we think we know about Henry VIII is just that – fable. We think of him in stereotypes. In 2007, in her column in The Observer, Victoria Coren wrote with heavy sarcasm, ‘if you type ‘wife-killing’ into Google, the first listing is a reference to Henry VIII, of wife-killing notoriety. Oh, that Henry VIII’. Popular perceptions of Henry VIII, according to the focus groups consulted by market research agency BDRC for Historic Royal Palaces, are that he was a fat guy who had six, or maybe eight wives, and that he killed a lot of them. In April 2007, next to a tomb in Christ Church Cathedral, where the heads of female figurines had broken off, I heard one man comment to another, ‘Henry VIII has a lot to answer for, hasn’t he?’ Myths and half-truths have also accrued around Henry VIII through the distorted pictures given by filmmakers. Each film makes its own Henry VIII, and so films about the king tell us far more about the preoccupations of each generation of filmmakers than they do about Henry VIII’s character. Recent scholarship has shown that the Henry of the 1930s, 1960s and 2000s differ wildly because they were designed to appeal to the very different cultural imperatives of each era. Charles Laughton’s Henry of 1933 in The Private Life of Henry VIII was an immature, sexually coy, sympathetic victim of his wives’ machinations. Made for a culture that revered royalty, he is a comic, overly sentimental man-child, to be pitied and petted. By 1969, in Anne of the Thousand Days, Richard Burton could play Henry as a good-looking, suave, alpha male. He may have been arrogant and self-centred, but this was the pre-feminist, James Bond era – such a macho, lovable rascal was an unproblematic hero. In the 21st century, Henry VIII changed again. Still an alpha male, this time Ray Winstone played him as a gangster-king, ‘the Godfather in tights’, according to the series director Peter Travis. Winstone’s Henry mixes sensitivity with aggression, he’s easily led, has temper tantrums, and can be brutally aggressive, as in the disturbingly fictitious rape scene that writer Peter Morgan also added to the more recent film, The Other Boleyn Girl. As reviewer Mark Lawson noted when the series came out, this Henry VIII responds to sexual politics after the revolution – it is hard on Henry and soft on his women. The Tudors plays into the zeitgeist in another way. Testament to a cultural obsession with male body image, Jonathan Rhys-Meyers’s Henry VIII looks like David Beckham, but is otherwise characterised very similarly to the infantile king of The Private Life. Henry VIII’s silver screen appearances have seeped into the collective consciousness – but this doesn’t make them any more reliable, or true as representations of an historic figure. Another thing obscuring our relative ignorance about Henry VIII as an individual is that what we mistake for knowledge about Henry VIII is often actually more accurately knowledge of what was around him. This year will see a spate of biographies of Henry VIII to mark the 500th anniversary of his accession and coronation, but it is striking that hitherto it has been his wives, courtiers and children who have been constantly revisited. Even where the information was more specifically Henry-centred, it is not rare to find a recap of his tumultuous marital history, a plethora of details about his court, or a catalogue of his activities substituting for a true understanding of his character and motivations. That Henry VIII was a warrior or jouster only sheds light on his personality when we understand the cultural significance of these activities. Henry VIII has seemed like a rather large void at the centre of a maelstrom of information about early Tudor society. Finally, perhaps the greatest problem with the primary popular impression of Henry VIII’s character is that is immutable. To understand a king who reigned for 38 years through one clichéd snapshot that is not dynamic and does not show change over time is hardly credible. Too often, we take our understanding of Henry VIII in his last days and use it as a blueprint for the rest of his life and his reign, ascribing to him, for instance, character flaws in his early years that were not manifest until much later on. As such, he has become a caricature, a cipher. So how can we get at a more profound understanding of this enigmatic man? There are obviously immediate problems with the notion of putting historical figures on the psychiatrist’s couch. Even ignoring the fact that the approach could, at worst, be thoroughly anachronistic, historians lack the sort of evidence that would most helpfully inform such a study. We have limited access to Henry VIII’s thoughts, motivations and emotions – there are, for example, no helpful confessional diaries over the period of Anne Boleyn’s arrest and execution. Leading historian Eric Ives has called Henry VIII’s psychology ‘the ultimate unresolvable paradox of Tudor history’. Yet, we do have many contemporary reports of Henry VIII’s behaviour and speech, such as those of the Imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys. We have also some of Henry VIII’s letters and the theological treatises he worked on, and we possess a whole panoply of state papers, royal proclamations and Acts of Parliament. We can also situate the man in his time: historical knowledge about the culture and attitudes of early Tudor England is quite far advanced. It is rare to have more information about the inner life of a monarch. Historians are, I believe, in a position to make cautious judgments about Henry VIII’s character based on existing evidence. My research for Hampton Court Palace in the run-up to our re-interpretation of the Tudor route to mark the 500th anniversary of Henry VIII’s accession in 2009 has suggested one fruitful way of getting to know Henry VIII. This is to recognise, and seek to understand, the stark differences between the early and the later king. Henry VIII’s accession in 1509 was famously received with rapturous praise running to hyperbole. William Blount, Lord Mountjoy wrote in a letter to Desiderius Erasmus on 27 May, When you know what a hero [the king] now shows himself, how wisely he behaves, what a lover he is of justice and goodness, what affection he bears to the learned, I will venture that you need no wings to make you fly to behold this new and auspicious star. If you could see how all the world here is rejoicing in the possession of so great a prince, how his life is all their desire, you could not contain your tears of joy. The heavens laugh, the earth exults, all things are full of milk, of honey, of nectar. Avarice is expelled from the country. Liberality scatters wealth with bounteous hand. Our King does not desire gold or gems or precious metals, but virtue, glory and immortality. In the wake of the commentary on Barack Obama’s presidency, it is not difficult to understand the tendency to such highfalutin remarks in the inaugural period of the new reign. Nevertheless, as a young man, and for at least the first twenty years of his reign (he was just weeks away from turning 18 when he became king), Henry was consistently and unequivocally judged to be peerless in appearance, aptitudes and accomplishments. For a start, Henry was clearly good-looking. Venetian ambassador Sebastian Giustinian described him as ‘the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on’ and remarked on his ‘round face so very beautiful, that it would become a pretty woman’. Chronicler Edward Hall rhapsodized that, The features of his body, his goodly personage, his amiable visage, princely countenance, with the noble qualities of his royal estate, to every man known, needs no rehearsal, considering that, for lack of cunning, I cannot express the gifts of grace and of nature that God has endowed him with all. Henry was gifted in other ways too. He demonstrated great intelligence and mental acuity. Erasmus wrote glowingly that even ‘when the King was no more than a child… he had a vivid and active mind, above measure to execute whatever tasks he undertook… you would say that he was a universal genius’. As a skilful linguist, Henry spoke French, Spanish and Latin. He was also a talented musician and composer. To entertain a visiting embassy from France in July 1517, Henry sang and played on every musical instrument available. In his report on the event, Francesco Chieregato, the Apostolic Nuncio in England, remarked that Henry was ‘a most invincible King, whose acquirements and qualities are so many and excellent that I consider him to excel all who ever wore a crown’. Henry’s achievements also extended to all masculine physical activities. Ambassadors noted how beautifully he danced, whilst an observer of the 1513 campaign against France recalled seeing the king practising archery with the archers of his guard, and how ‘he cleft the mark in the middle, and surpassed them all, as he surpasses them in stature and personal graces’. He was fond of tennis, ‘at which game it was the prettiest thing in the world to see him play; his fair skin glowing through a shirt of the finest texture’, and was also ‘a capital horseman, and a fine jouster’. Henry delighted in hunting, tiring eight or ten horses a day before exhausting himself. Sebastian Giustinian judged Henry VIII in 1515 as not only very expert in arms, and of great valour, and most excellent in his personal endowments, but … likewise so gifted and adorned with mental accomplishments of every sort that we believe him to have few equals in the world. This energetic attitude towards sports was an essential part of his character, and his youthful ebullience was sustained throughout his twenties and thirties. Contemporary reports suggest that Henry was spirited, mirthful and exuberant, ‘young, lusty and courageous… [and] disposed to all mirth and pleasure’. He devoted his time to the pursuit of fun, and revelled in entertainments, masques, banqueting and merry-making. Court festivities were held on an astonishingly grand and lavish scale. To mark May Day in 1515, the king and his guard gathered at a wood near Greenwich Palace dressed all in green as Robin Hood and his merry men. Attended by 100 noblemen on horseback who were ‘gorgeously arrayed’, singers and musicians playing from bowers, and sweetly-singing birds amassed for the occasion, Henry’s court enjoyed a sumptuous open-air banquet, before processing back to Greenwich for a joust. Such flamboyance was also reflected in the magnificent finery of his wardrobe. The records that Maria Hayward has recently unlocked for us include frequent references to brocade, ermine, satin, velvet and huge, conspicuous jewels, including a round cut diamond that was described by one observer as ‘the size of the largest walnut I ever saw’. As Henry was extremely charismatic and had great stage-presence, this combination of boisterousness and opulence was strangely compelling. Perhaps most surprisingly of all, commentators almost universally described his nature as warm and benevolent. In 1519, summing up four years at the English court, Giustinian enthused about how Henry was so ‘affable and gracious’, a man who ‘harmed no one’. Ten years later, Erasmus would call him ‘a man of gentle friendliness, and gentle in debate; he acts more like a companion than a king’. Henry VIII appears, in his early years, to have been friendly, affectionate and very generous in gifts and attention. What a contrast this is to reports of Henry VIII in later life! The most obvious change was in the king’s appearance. Between the ages of 23 and 45, his waist and chest measurements had increased gradually from 35 to 37 inches, and 42 to 45. After his 45th birthday in 1536, he very quickly became gross – by 1541, his waist measured 54 inches, his chest 57. But this was the least of the changes. Instead of being known for the ease of his companionship and gentle graciousness, the older Henry VIII was reputed to be irritable, capricious and capable of great cruelty. Comments were made about his increasing irascibility and ‘mal d’esprit’, ‘the King was irritated and … his ministers were at a loss to account for it’, or his mercurial unpredictability, ‘people worth credit say he is often of a different opinion in the morning than after dinner’. His volatile moods were a source of anxiety for his counsellors. He was violent with some – he would ‘beknave’ Thomas Cromwell twice a week, hitting ‘him well about the pate’. Others he berated – after Cromwell’s death, Henry blamed his advisers for having ‘upon light pretexts, by false accusations… made him put to death the most faithful servant he ever had’. Some of this stemmed from the inflamed condition of a varicose ulcer in his leg, probably re-opened by a jousting accident in 1536. This ulcer brought him constant and debilitating pain, together with infections, fevers and discharges that produced a putrid smell. This undoubtedly had an impact on his temper, although cannot in itself explain it all. By 1540, Charles de Marillac, the French ambassador, would describe Henry VIII as fearful, inconstant and ‘so covetous that all the riches in the world would not satisfy him’. According to Marillac, Henry’s inability ‘to trust a single man’ meant that ‘he will not cease to dip his hand in blood’, and ‘every day edicts are published so sanguinary that with a thousand guards one would scarce be safe’. Such savagery was a particular feature of Henry VIII’s reign after 1536. There are some notable exceptions from early in his reign, but Henry’s tendency towards the cruel dispatching of those who had wronged him – including those very close him – reached its apogee in his last decade. The method of dealing with miscreants also changed. After 1536, of all the high-status individuals executed at the king’s behest, only the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace and the conspirators of the Exeter plot were tried and executed by judicial process. Everyone else of high status accused of high treason was convicted and executed on the basis of parliamentary attainder – that is, an act passed through parliament that declared the accused guilty and condemned them to death without recourse to a common law trial. Attainders did not need to cite specific evidence or name precise crimes. Victims of this method included Henry’s erstwhile closest confidant and chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, his fifth wife, young Catherine Howard, and the septuagenarian Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, whose death when ‘so infirm and weakened by interrogation that she had to be carried to the scaffold in a chair’, Greg Walker has called ‘the nadir of royal vindictiveness’. Despite her royal blood, she was clearly no real threat to the realm. Henry had become a misanthropic, suspicious and cruel king, and his subjects began (discreetly, for such words were illegal) to call him a tyrant. In his early years, Henry’s charisma and egoism had been directed into a little showing-off while jousting (on one occasion he presented himself before the queen and the ladies with ‘a thousand jumps in the air’), but the ends to which these qualities were now deployed had changed. Now they fuelled a vastly more repressive and harsh regime towards those who disagreed with him. The idea of a king whose life was a tale of two halves helps enormously in reaching a more accurate understanding of Henry VIII’s character. The next challenge is to work out how, when and why this change occurred. Scholars have suggested a variety of psychological turning points. Miles F. Shore, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, plumped for 1525-7, when he hypothesized that Henry had experienced ‘a crisis of generativity’ caused by the reality of middle age to live up to his youthful narcissistic fantasies of omnipotence. Sir Arthur Salisbury MacNulty, MD, suggested around 1527 and linked this a head injury sustained by Henry in 1524. He cautiously reasoned that a cerebral injury could explain Henry’s shift in behaviour and character from Jekyll to Hyde. Psychologist J.C. Flügel positioned the change around 1533, when he thought that Henry had undergone ‘a marked transformation’ and become ‘vastly more despotic’. To me, the evidence suggests that we should consider a slightly later date. Although the change was partly the result of a cumulative process, the year 1536 contained all the ingredients necessary to catalyse, foster and entrench this change. It was Henry VIII’s annus horribilis. In the course of one year, Henry suffered threats, betrayals, rebellion, disappointments, injury, grief, and anxieties on a terrific scale. A near-fatal fall from his horse in January 1536 left this great athlete of the tiltyard injured and unable to joust again, when for Henry, the pursuit of physical masculine activity was strongly linked to his sense of self. This injury was also the key to his later obesity. Henry’s wife, Anne Boleyn, suffered a miscarriage of a male child on the same day as his first wife’s funeral. Only months later, Anne was ‘discovered’ to be an adulteress with a number of men of the king’s Privy Chamber, and the confession of a key defendant provoked her rapid arrest, trial and execution on 19 May. Almost immediately, Henry remarried, to Jane Seymour (Hans Holbein’s famous and hugely influential portraits of the pair date from this time). In July, soon after Henry had forced his daughter Mary to swear to her own illegitimacy, Henry’s only son, the illegitimate Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset, died aged 17 – leaving the king entirely heirless. Worst still, in October, a series of linked uprisings formed the largest peacetime rebellion against an English monarch, which Henry’s small armies could not have defeated if it came to battle, and the pope issued a bull which threatened to make the invasion and overthrow of Henry’s throne legitimate. Henry responded to all these blows by extreme reaction – decisively acting to re-assert his power and raging against his enemies – but he was, nevertheless, broken by the tumultuous events of this one year. Understanding how and why Henry VIII changed will finally help us to solve the riddle that is this mysterious and inscrutable king.

Further reading: Lacey Baldwin Smith, Henry VIII: The Mask of Royalty (St Albans, 1971) Thomas S. Freeman and Susan Doran, Tudors and Stuarts on Film: Historical Perspectives (Cambridge, 2009) Maria Hayward, Dress at the Court of King Henry VIII (Leeds, 2007) Suzannah Lipscomb, 1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII (Oxford, 2009) David Starkey, Henry: Virtuous Prince (London, 2008) Greg Walker, The Private Life of Henry VIII (The British Film Guide 8, London, 2003) Alison Weir, Henry VIII: King and Court (London, 2001) Derek Wilson, In the Lion’s Court: Power, Ambition and Sudden Death in the Reign of Henry VIII (London, 2001) |

|